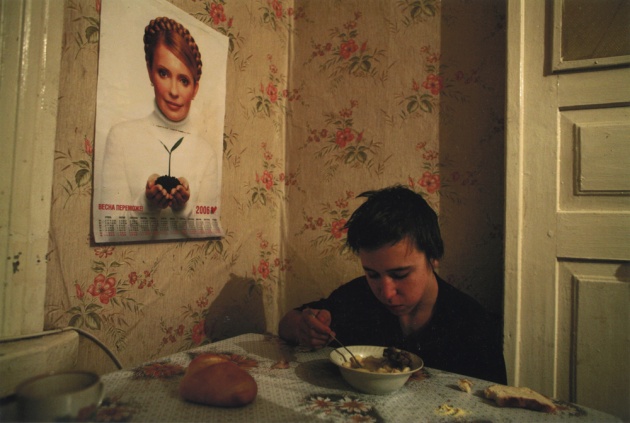

Donald Weber

The Underclass and its Bosses

August 7, 2008 - August 31, 2008

In these photographs by Donald Weber, the industrial city of Dneprodzerzhinsk stands revealed as a real world dystopia that echoes and rivals the bleak visons in the movies Mad Max or Children of Men. The sudden collapse of Socialism in 1989, soon after the Chernobyl nuclear incident, created a spiritual crisis in the country. The moral vacuum was quickly filled by quacks and criminals. Gangs of criminals stole everything they could get their hands on: TV sets, apartment elevator motors, bronze manhole covers – entire factories, too. Nothing worked. The middle class fell. Powerful oligarchs built themselves fortified hill castles. The world turned upside down. With the fall of the Soviet Union, Ukraine’s state-educated middle classes – teachers, doctors, and scientists – grew jobless, impoverished. Hard men with secret connections bought up government-owned factories for cheap. These photographs reveal the underbelly of globalization.

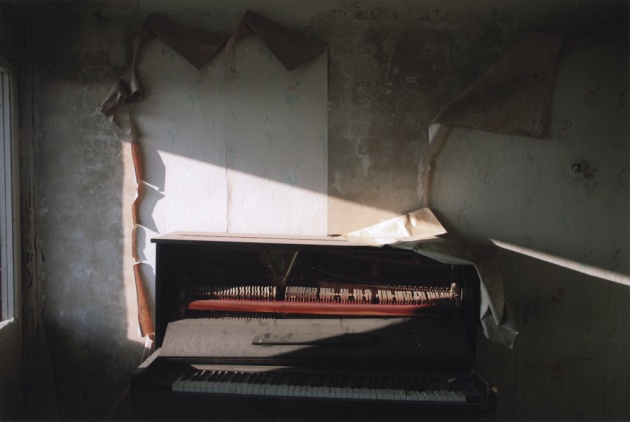

Bastard Eden

On April 26, 1986, as the plume of radioactive debris fell across the land and into the rest of Europe, the authorities evacuated the city of Pripyat and created a 40-kilometer Exclusion Zone around it. The 50,000 residents had fifteen minutes to leave, and never returned. Today a ring of silent fire surrounds these pine woods and abandoned apartment buildings. People are not supposed to live in Chernobyl; wild boars, rabbits and deer thrive in the lush greenery. Even the steppe wolves have returned. Donald Weber began visiting this region to see what daily life was actually like in a post-nuclear world. He found a haphazard community of survivors and of emigrants from other cities, who told him they preferred Chernobyl’s rural peace to the urban blight of Ukraine’s industrial zone. The residents were happy to invite him into their homes, sharing their food and strange stories. Were they afraid of dying early? No, people told him, they were afraid of modern life. The matter-of-factness about the continued fertility of the despoiled landscape is both thrilling and terrible.